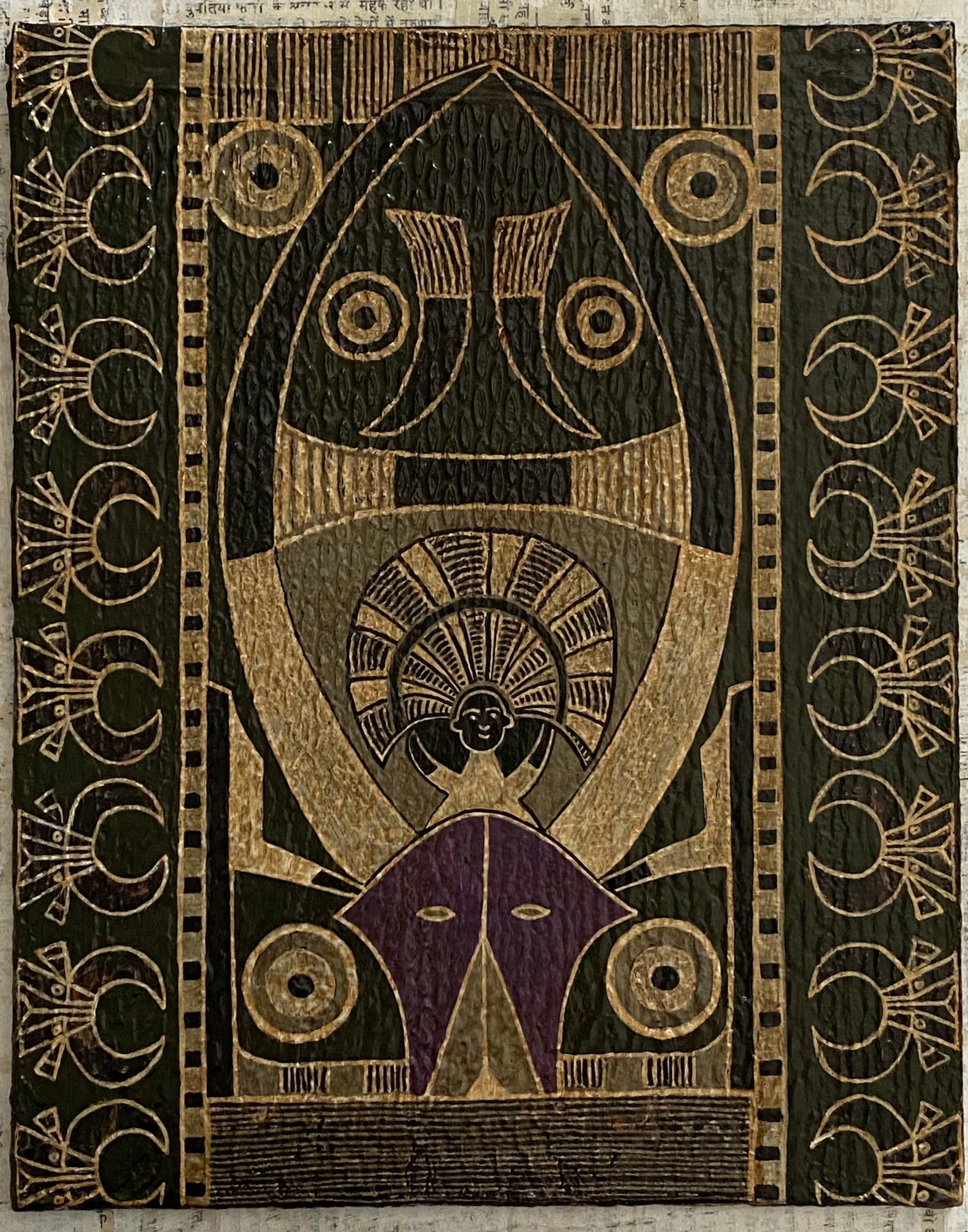

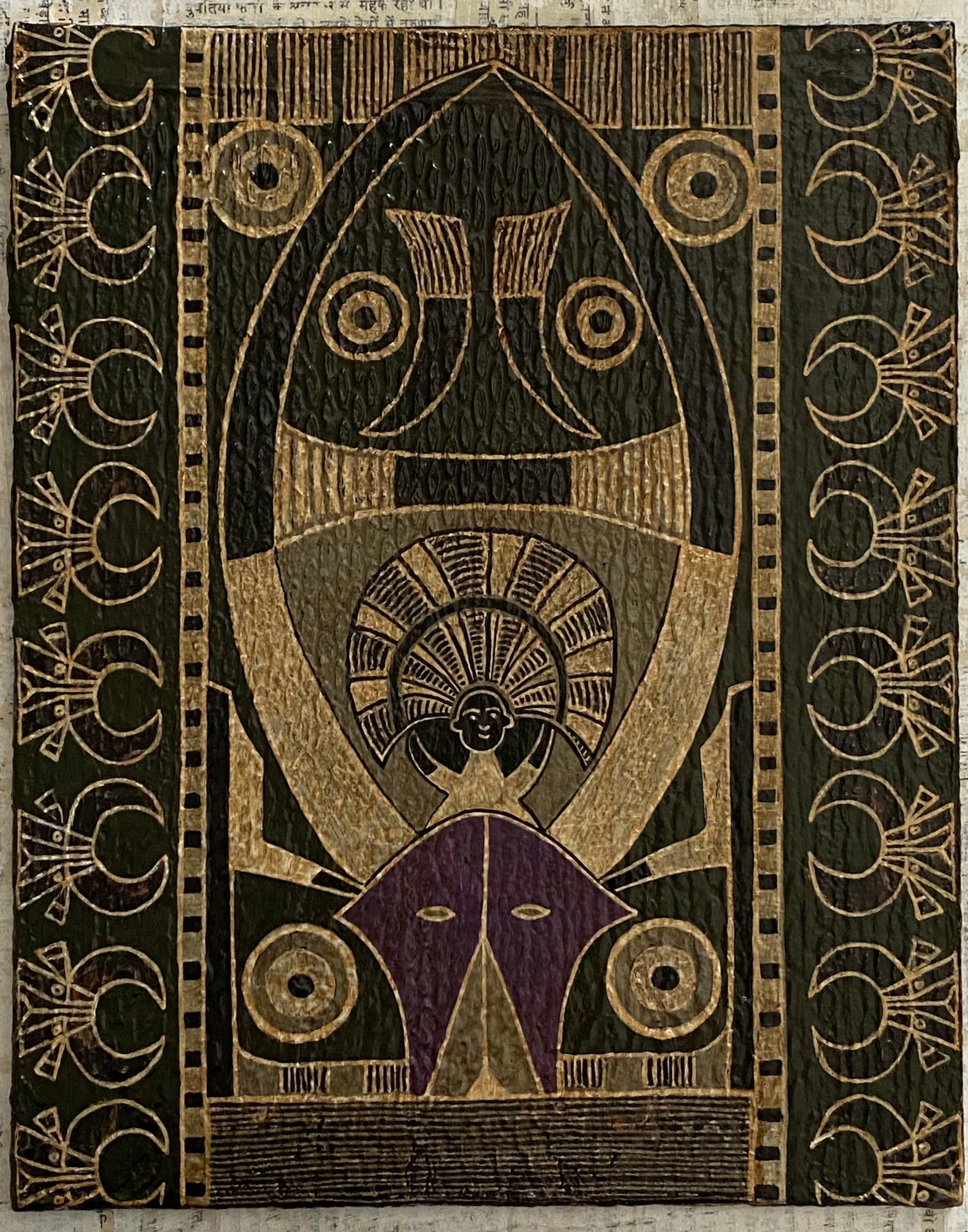

The Kurmi tribe, through the use of glyptic art depicts Lord Shiva/Pashupati (Lord of the animals) as a horned deity on the back of an animal.

One of the oldest art forms of tribal art which has continued since 4,000 BC. Mud murals are an integral part of the domestic architecture of Jharkhand in eastern India.The name ‘Sohrai’ is said to have derived from a Paleolithic age word—‘soro’, meaning to drive with a stick.The Sohrai festival is celebrated one day after Diwali, and the Sohrai art form is handed down from mother to daughter. These paintings are considered auspicious symbols related to fertility and prosperity of the harvest. There are four major painting techniques- scraping with fingers, scraping with broken pieces of combs, twig-brush and cloth swab stencil or glyptic paintings. It is a symbolic and sacred art form of signs that carry multiple meanings. After the monsoon season, the mud houses have to undergo an renovation with many layers of colored clay. Black mud represents the womb, and the white mud represents god, sperm and light. When the white is covered entirely over the black earth and cut with a comb, the result is seen as a transformation of inert earth into an expression of the mother goddess.Once the mud wall surface is prepared, the motifs are painted in red, ochre and black.The red line is drawn first as it represents the ‘blood of the ancestors’, procreation and fertility. The next line is black which signifies eternal dead stone and mark of the God, Shiva. The next all-encompassing outer lines stand in their traditional values of protection, fidelity, and chastity. The white is painted with the last year’s rice, grounded with milk into gruel, this represents food.In case of elaborate designs of the Kurmi tribe, the designs are first drawn on the wall using a nail or similar sharp object. After this, the designs are painted using the frayed and softened edge of the chewed Neem tree twig allowing the artist to produce lines and dots on the walls. Popular Sohrai motifs are animals, birds, lizards, elephants and Pashupati.

It is common practice for the tribal women of Hazaribagh (Jharkhand) living in forested hill villages and agricultural valleys to paint murals in preparation for weddings. Such paintings are known as Khovar where Kho is cave and Var a bridal couple. Sohrai and Khovar paintings are stylistically the same, however they commemorate different occasions. As said earlier Sohrai paintings are made in the harvest season in winter. Khovar paintings are made during weddings. These paintings are marriage mural art to decorate the bridal chamber. During the harvest as well as the marriage season the women decorate their houses with beautiful large murals of jungle animals and birds, and exotic plant forms, as if bringing the forest indoors. The Ganju houses at Saheda have their own distinctive and unique form of wild and domestic animals and birds forms like peacocks, elephant, tiger, crocodile, snake, jackal, and plants depicting the pictures as a story.

Women artists of the Ghatwal and Agaria communities paint murals using a stencil-type method using kaolin creamy white clay obtained from forest streams, hematite red- oxide iron-ore, and manganese black earth colour found in the hills. The Sohrai harvest murals are a feast for the eyes revealing labour of love done by traditional women artists after repairing, re-plastering, and painting the village mud house walls with cloth swabs daubed in liquid earth colours sometimes taking two weeks to paint the entire household, and courtyards. The wall is segmented into large rectangular panels when the kaolin clay layer is applied. Then, using a darker red or black clay, women paint the negative spaces within the panel, leaving some areas white which form the animal or plant motif. The technique is complicated since it requires the artist to visualize and paint not the motif but the space surrounding it. The Sohrai-khovar art painted on the mud walls is a matriarchal tradition handed down from mother to daughter.

According to the Santhal mythology, Marang Buru (God of the mountains), Jaher Ayo (goddess of the forest) and the elder sister of the Santhals, would descend on earth from heaven to pay a visit to their brothers and to commemorate this the Sohrai Harvest festival is celebrated and the Santal women decorate their walls with bright geometric murals of Sohrai art. The Santal mural colors and patterns of the Singhbhum region is brighter than that in the Hazaribagh region because the types of clays found in the two regions in Jharkhand differ in mineral content and therefore in pigmentation, leading to two distinctive colour palettes. Singhbhum has brighter colour clays with the murals painted in deep rust, ochre, black and light blue colours and Hazaribagh is dominated by black manganese-rich clay, the nearly white kaolin clay and the occasional use of reddish coloured clays. The difference is further heightened by the use of artificial paints and paint brushes which is much more common in Singhbhum as it is a highly industrialised region and Adivasi and non-Adivasi villagers have been employed by local industrial establishments for generations. Santal women in Hazaribagh paint lengths of geometric patterns and have a restricted colour palette red and black. These are painted using the cloth, and attention is paid to achieving very precise edges to produce a sharp geometric mural.

Jharkhand has heavy monsoons and the mud houses “maati-ghar” of the region are repaired and re-plastered after the rainy season. The preparations begin with the reworking of the wall surface. the final mural produces a smooth surface that works to largely repel water or at least ensure that it flows down and does not penetrate and weaken the earthen wall. In this way, the practice of painting murals becomes integral to the preservation of the mud houses. Sohrai art is a “Parampara” tradition carried on and taught from generation to generation by women artists.

The village of Isco adjoin the rock-art (10,000 B.C) sites in the Sati hills where the Munda tribal women paint the similar pre-historic designs on the house walls giving it a symbiosis with the art. The Munda paint or scrape with their fingers in the soft-wet earth of their houses, using unique motifs such as the rainbow snake (Lorbung) and plant forms of a deity similar to the Prajapatis and Kurmis. They commonly spot their painting with vermilion and white dots. First the designs are cut in mud clay and then filled in with white markings, and vermillion.

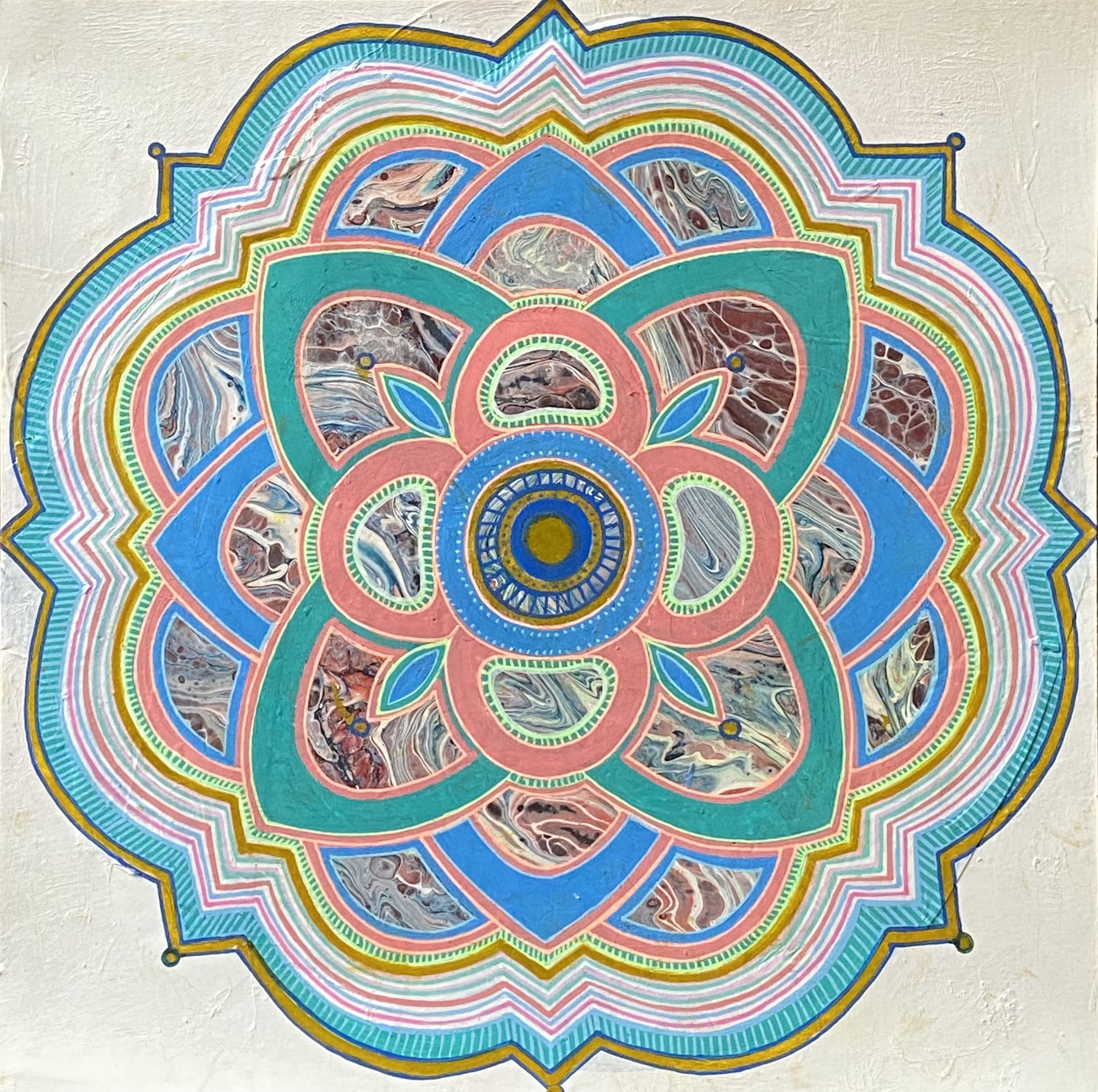

Sanjhi, floor art is considered to be one of the finest arts of spiritual expression. Created in the temples dedicated to Lord Krishna, as part of a fifteen-day autumnal festival as well as to an annual ritual “Pitra paksha” the period of the ancestors and the departed. Contemporary evidences show the early use of stencils cut out in banana leaves later moved to paper was then taken to its glory by the Vaishnava temples in the 15th and 16th century. The most common type of temple Sanjhi is made of colored powder on an earthen platform (Vedi). Another type is created from dry colors on water “Jal Sanjhi” and underwater respectively.

The preparation of intricate design stencils “sancha or khaka” carefully cut with small special scissors, demands a considerable amount of time, patience and effort on the part of the artist, paired with high artistic proficiency. The theme for the Sanjhi stencils are derived from Krishna-lila and the Bhakti movement. The development of this art form, its migration from U. P. to Rajasthan and the Mughal influence visible in it is fascinating.

Different from other rangoli floor art, Sanjhi starts on the outer edge border and moves inwards to the central portion. The most elaborate Sanjhi art is made by the temple priests with stencils that are superimposed on each other and filled with powders of different colors until the final pattern appears. The final image then presents a more complex design and depth.

Sanjhi is created on an earthen platform or “Vedi”, which is octagonal or in the shape of eight-pointed star. Colored powder is pushed through a cloth with the fingers onto a stencil placed on the Vedi. Whole series of stencils are used; creating a sequence of patterns layered one over the other, like a printing process, resulting in the final image having intricate design and depth. The “Hauda” (heart) or the central portion of the Sanjhi, constitutes the sanctum sanctorum, encircled by interlocking decorative patterns requires considerable time and effort and is entrusted to specifically trained professional artists associated with the temple tradition as hereditary Brahman priests.

The Warli or Varli are an indigenous tribe living in mountainous as well as coastal areas along the Maharashtra-Gujarat border. Women are mainly engaged in the creation of these paintings. In this art form, chewed bamboo stick brush and mixture of rice paste and gum binder is used for white paint. They have a very basic graphic vocabulary: a circle, a triangle and a square. The circle and triangle come from their observation of nature, the circle representing the sun and the moon, the triangle derived from mountains and pointed trees. Humans and animals are represented by two triangles joined at the tip. Their precarious equilibrium symbolizes the balance of the universe. It is rare to see a straight line in Warli paintings it is shown as a series of dots and dashes. The square is a newer addition, indicating a sacred enclosure or a piece of land but when used for a ritual painting, the central motif-a square, known as the "chauk" or "chaukat”. The harmony and balance depicted in these paintings signify the harmony and balance of the universe.

Painted white on red mud walls, they are similarto pre-historic cave paintings and usually depict scenes of human figures engaged in activities like hunting, dancing, sowing and harvesting created in a loose rhythmic pattern. They do not depict mythological characters or deities, but depict the tribe’s daily social life. One of the important aspects within Warli paintings is the “Tarpa dance” – the tarpa is a trumpet-like instrument, which is played in turns by different men. While the music plays, men and women join their hands and move in a spiral form around the tarpa players. This circle of the dancers symbolise the circle of life.

Saura wall painting called ikons (ekons) painted by the Saura tribes in Odisha and hold religious significance for the Sauras. Ikons were originally painted on the walls of the huts by the high priests (Kudangs) where the base color is red or yellow ochre earth. Then motifs are painted on using tender bamboo brushes shoots. Each painting has a rectangular frame and a house-like structure with different levels and no block is left empty. People, horses, elephants, the sun and the moon and the tree of life are recurring motifs in these ikons. Ekons use natural dyes and chromes derived from ground white stone, hued earth, and vermilion and mixtures of tamarind seed, flower and leaf extracts.

The Saura paintings have a striking visual resemblance to Warli art but they differ in both their style and treatment of subjects. Warli paintings have a red background and patterns and figures are drawn in white, figures are not well organized and highlight themes like festivals, dancing, hunting, fishing. Figures are equilateral triangles where male and female icons are clearly distinguishable whereas Saura paintings can have a red, white, or yellow background and the lines and patterns are drawn in white, red, yellow and black. It depicts religious matters, and its connections with nature and human. It uses a fishnet approach of painting from the border inwards, well organized in levels, the figures are larger and elongated, Saura women are represented with two triangles, while the men are shown with just the upper triangle while the lower half is projected on horseback, playing the drums etc.

Kurumba art is a unique tribal art form found in the Nilgiris or “blue-mountains” (Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu). Kurumba is a tribe of hunters and medicine men, their art is primarily ritualistic describing various facets of tribal life in the remote forests of the Nilgiris. Originally, they drew with burnt twigs and colored the art with a resin extracted from the bark of the Kino tree. Kurumba art is traditionally practiced by the male caretakers of the temple, or the priests of the Kurumba tribe paint on the outer wall of the temple and the house.

The figures are made up of lines and are minimal in style representing their gods, Kurumba beliefs and the milestones of the village. There is an unusual depth created in these paintings by the way the background is painted. The figures slowly decrease in size as things move further and further away from the foreground. The background color usually ranges from shades of brown and green, whilst the figures are commonly dark brown or black. There are also bushes and shrubs drawn at regular intervals to show the natural beauty around the village. The colors used are yellow, brown, black, green, white and orange. A piece of cloth as well as cut and shaped bamboo sticks serve as brushes, sometimes along with the feathers of the wild fowl used to apply the colors on the prepared walls.

Kurumba paintings are similar in many ways to the Warli paintings in their themes and representation. The only difference is that the figures are flat with rectangular bodies, the women are recognized by the bun on their head. There are hardly any patterns used and it looks like a painting and not like a decorative patterned art like in Warli or Saura art.

The snake-goddess Manasā is shown at the centre of the painting rising up out of the head of a cobra, naga; she is surrounded with sprigs of foliage with brightly-coloured leaves. She wears a hair ornament, earrings, a nose-ring, a necklace, bracelets and upper-arm bands. The body of the snake winds it way around the body of the goddess in a concentric series of ovals; the tale is seen in the bottom left-hand corner. The other corners are filled with branches also with brightly-coloured leaves.

Madhubani, an ancient style of folk art painting that originated 2500 years ago in Mithila region of Bihar. Traditionally women used to paint Madhubani art on freshly plastered mud walls of huts to celebrate occasions such as religious festivals, births, and marriages. The themes and motifs of Madhubani are drawn from mythology, rituals and local flora and fauna.

Some of the main attributes of all the Madhubani paintings are the double line border, ornate floral patterns, bright colours, intricate details and patterns, abstract-like figures of deities and bulging eyes and a jolting nose on the faces of the figures.

Bharni, Kachni or Kayastha, Godhana and Tantric are the different styles within this art form. These paintings were made using brushes, fingers, twigs, pen-nibs and bamboo sticksas well as natural colours that were sourced from the paste of powdered rice, natural dyes, and plants.

Gond art is folk and tribal art, practiced by one of the largest tribes in India – the Gonds, predominantly from Madhya Pradesh. This community draws positive energy by surrounding itself with color and reverberates with a culturally distinct ethos and draws stimulation from myths, legends to images of daily life interlinked with nature, the surrealism of sensations, aspirations and imagination. The mythical beasts and the intricate detailing of flora and fauna are the dominant themes. The child like simplicity of these art works reflect the community’s own straight forwardness and how it is rooted in their folk tales and culture, as story-telling is a strong element of Pradhan Gond art. They believe that viewing a good image begets good luck and so they painted on the walls and floors of their house and are also called Digna and Bhittichitra paintings. These paintings begin from the base of the wall and reach up to the height of eight to ten feet. Lines are used in such a way to convey a sense of movement to still images. Dots and dashes are added to impart a greater sense of movement and increase the amount of detail. They use bright vivid colours derived naturally from objects such as charcoal for black, coloured soil for brown, yellow, white and red, plant sap, flowers for deep red, bean leaves for dark green and cow dung for light green. The painting is done with the help of a cotton swab or piece of cloth tied to the twig of neem or babul tree. One of the distinctive elements is the use of ‘signature patterns’ that is used to ‘infill’ the larger forms and every Pardhan Gond painter has developed his or her own signature style.

The Bhils, India’s second largest tribal community, live in Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra. The history of its art is as old and as veiled in mystery as the Bhils themselves. These ritualistic paintings were done by Badwas (holy priests) or specially appointed male members who convey their tribe’s stories, prayers, memories and traditions as beautiful images in a symphony of multihued dots onto the clay walls of their village homes using neem sticks and other twigs, and natural dyes such as turmeric, flour, vegetables, leaves and oil to derive brilliant colors.

The dots on a Bhil painting are not random. The first step to learning the Bhil art is the mastering of the dots is to skillfully repeat equal sized and uniform dots in rhythmic patterns and colors. These dots have multiple layers of symbolism as they are inspired by the kernels of maize (corn their staple food and crop). These patterns could be made to represent anything that the artists wish, from ancestors to deities. The work of every Bhil artist is unique, and the dot patterns can be counted as the artist’s signature style. The two most famous artists of the Bhil tribe are Lado Bai and Bhuri Bai. Nature, flora and fauna, rituals, festivals, Bhil Gods and Goddesses are something they paint in the old Bhil style. Instead of painting on mud walls now, the tribe have now moved to paper or canvases and these ritualistic paintings are even offered as gifts to gods and goddesses at the time of festivals.

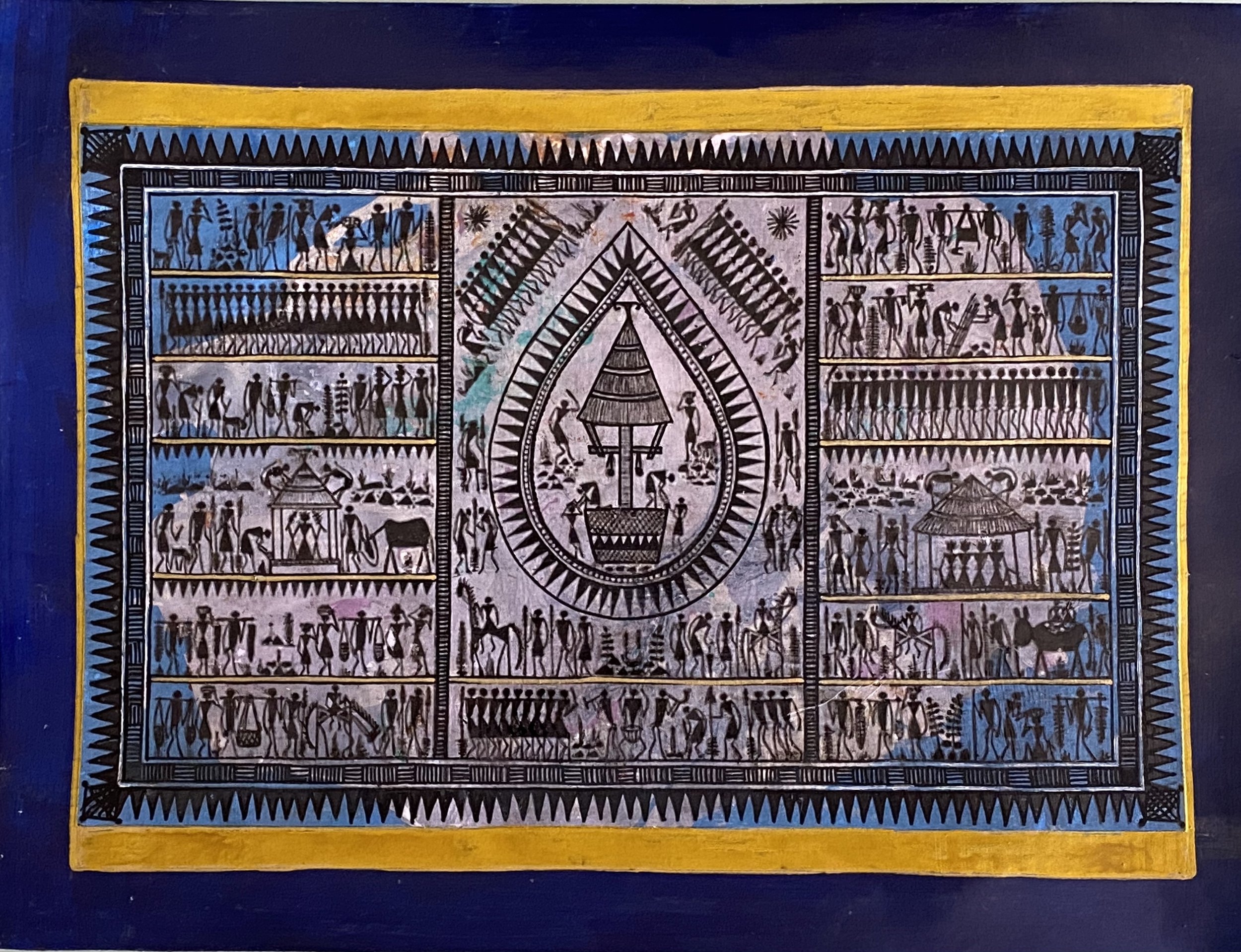

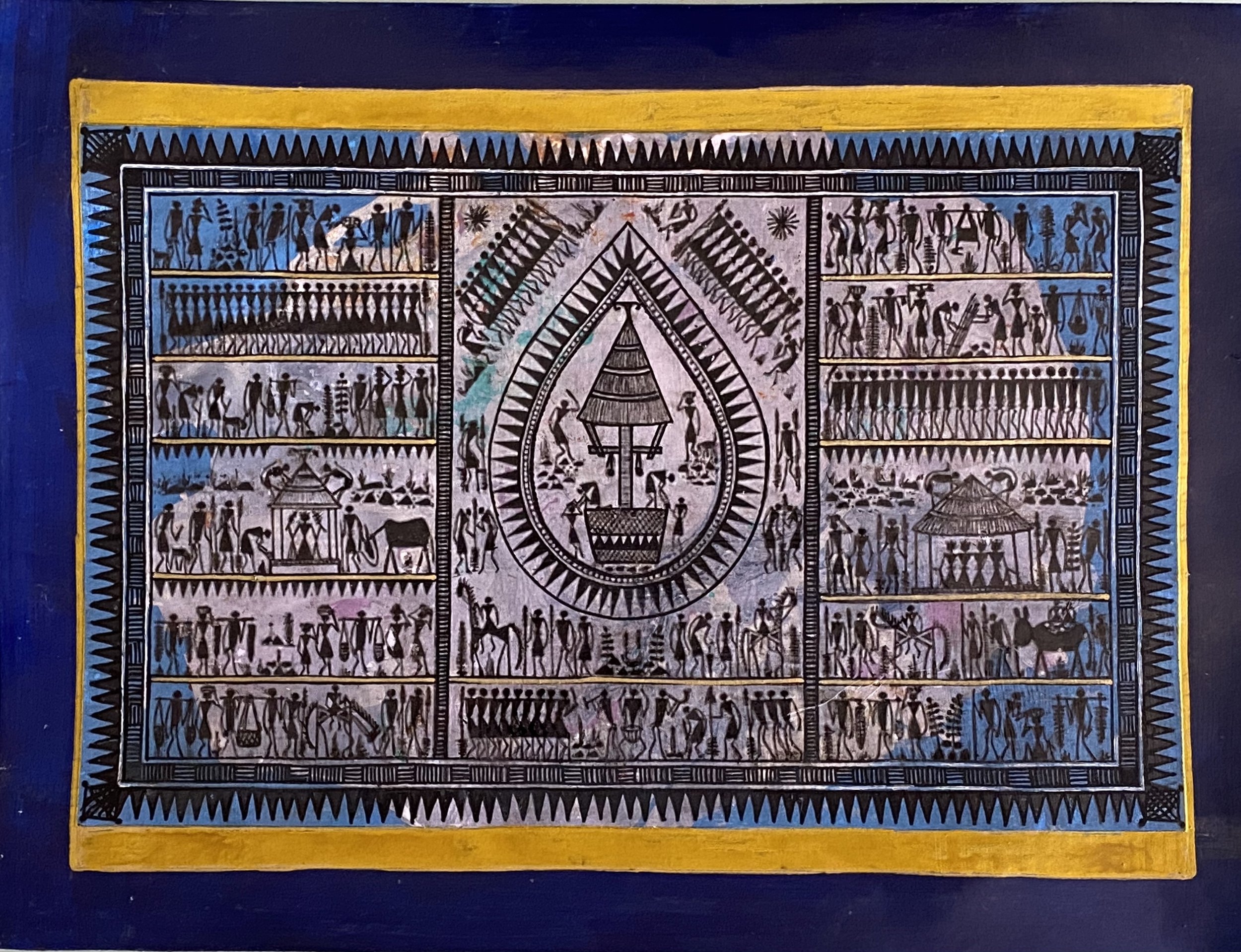

Deewaru, an agrarian tribe living deep in the forests of Karnataka, is a matriarchal society where women are highly respected and control most of the activities. This power relationship between men and women is also manifested in the social culture like wedding ceremonies where the bride's family commands higher respect. The community is culturally integrated by unique customs and ritualistic practices. These practices reflect their interaction and profound relationship with their environment. The traditions and ritualistic practices of the community are incomplete without the practice of Hase Chittara, a traditional folk art painted on the mud walls of their huts and always associated with a folk song. Chittara murals are intricate patterns that represent the auspicious ceremonies and rituals of life using several lines, segments, and symbols. The paintings are done free hand and usually 2 to 3 feet in size requiring understanding of geometry, ratios, and proportions, which the women of the community have been using with great dexterity. These murals are done basically in four natural colours, White (Rice Powder), Black (Burnt Rice Powder), Red (Laterite Soil) and Yellow (Pigment from the Gurige Flower) and the brushes are made of Areca nut fibre. While the designs are common across the entire community, the colours used distinguish one family or clan from another. Chittara bears a close resemblance to Warli art, but it can be distinguished by its elaborate geometric designs. The chittara shown here is called Hasegode which depicts the wedding and in the center is the wedding altar where the bride and the groom are seated.

Symbols of Hase Chittara by the Deewaru Tribe wedding ceremony

Yaileyh: the vertical or horizontal ‘lines’ which symbolize subtle attraction/intimate relationships, the Chittara painting cannot be started without these lines.

Nilee Kochu: is the cross hatching all throughout is the symbol of strength of teamwork or unity is strength.

Garagasa Saalu: the mountain border all around is the symbol of sharpness is. It implies that without being sharp in life it’s difficult to break through the obstacles.

Peeti/Pathanga: the square with the X in is the symbol of a Guest is a butterfly/a bee. In Hase Chittara paintings, the pair of Bees indicates the presence of abundant sexual desires during the married life.

Madhumaga & Madhnageethi: the Symbol of Eternal Bonding- In the center square is the bride with the bridegroom, an epitome of unconditional love.

Dhandigey: Symbol of Highness is the palanquin used to carry and to honor the Gods, kings and bride/bridegroom.

Maadhana Kai is the symbol of marital bliss as this is to invoke the lord’s blessing on the newlywed couples so that they have a blissful married life ahead.

Chanduvina Saalu: lines of marigold flowers are drawn in the chittara painting symbolize friendship promotes friendship between the two families.

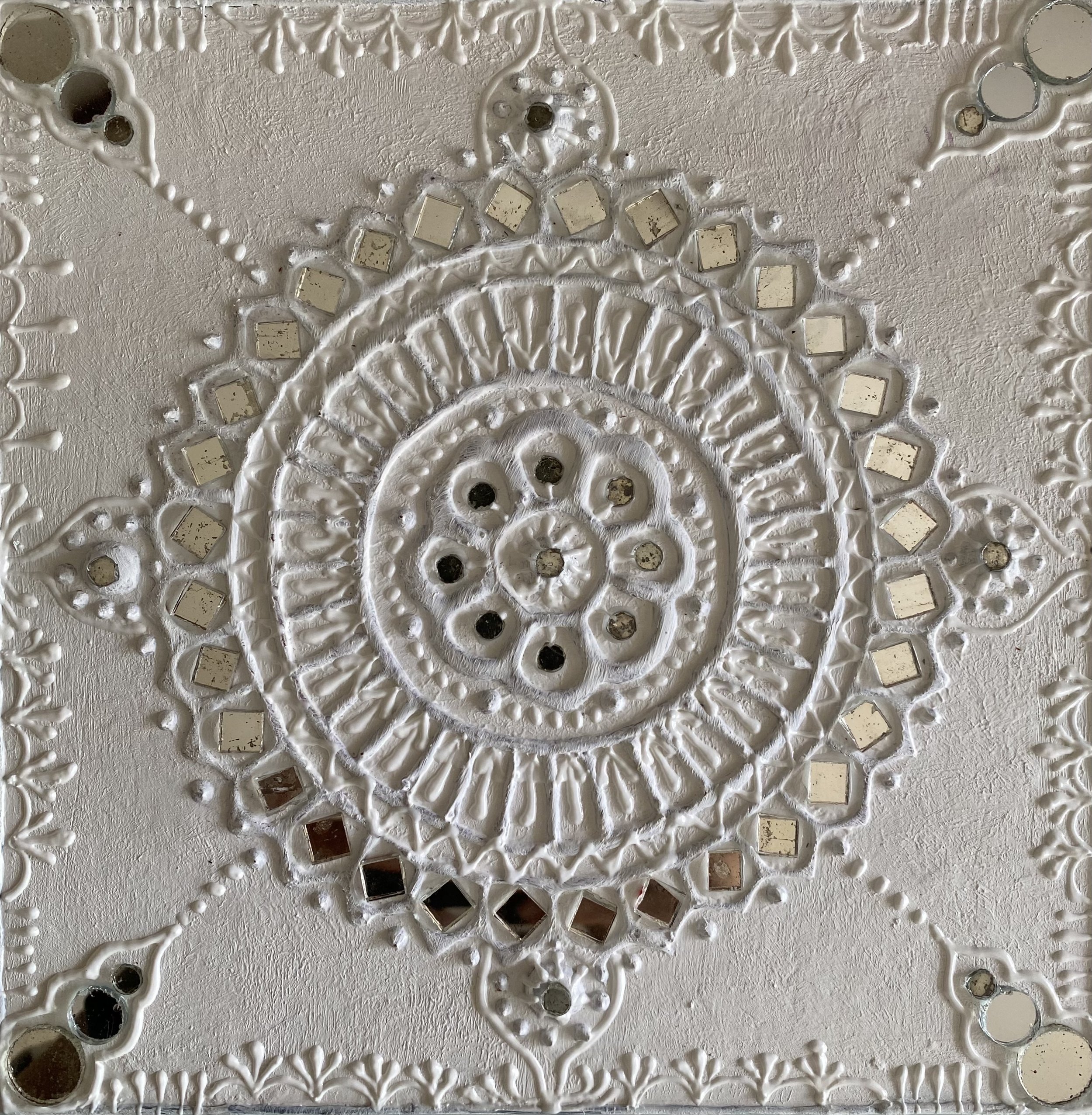

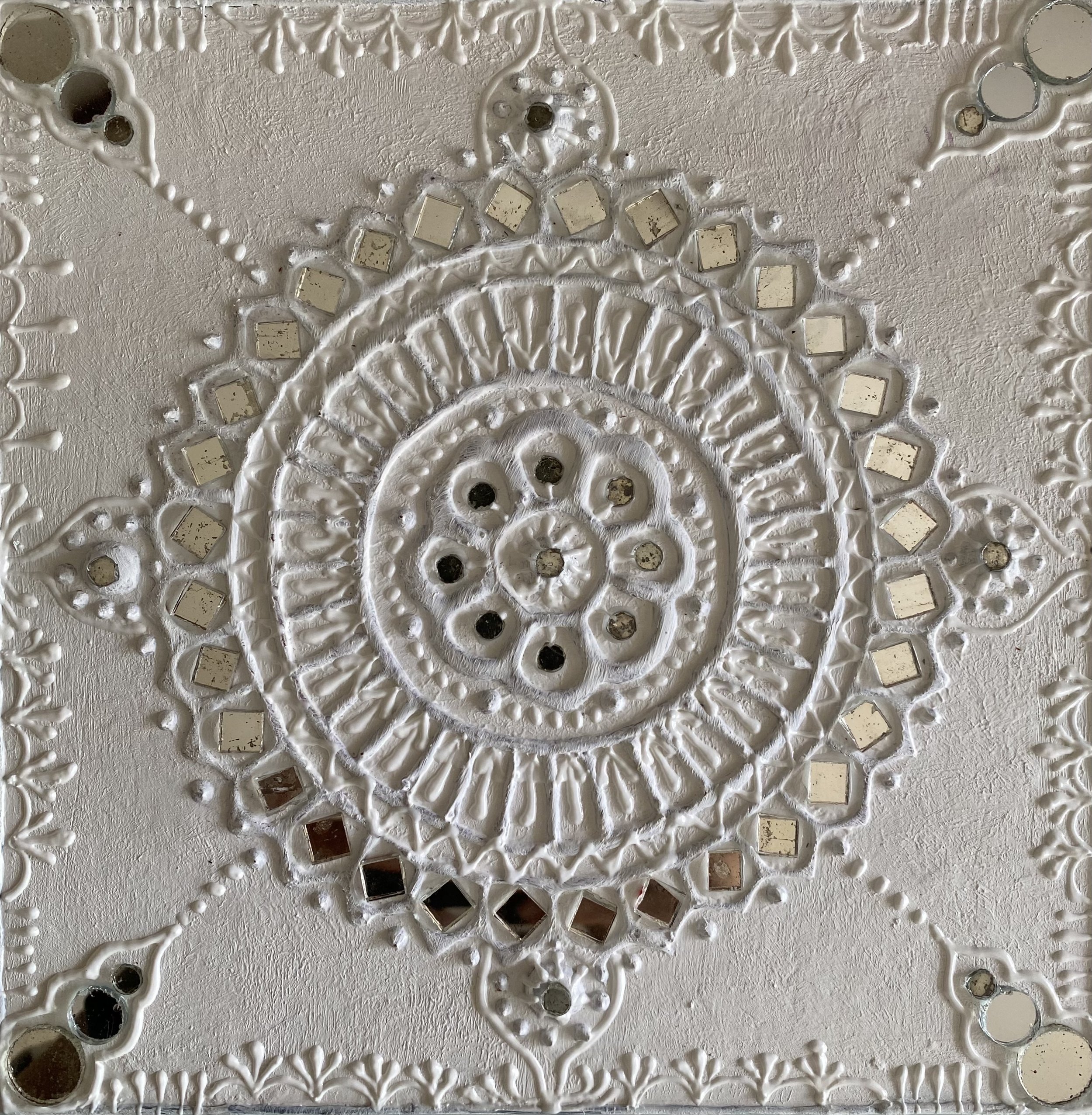

Mud and Mirror Work (Lippan/Chittar Kaam) is a traditional mural craft of Kutch, Gujarat. It is carried out by the women of the Rabari tribe and the Meghwal community whereas by men in the Mutwa community who live in circular mud houses known as “Bhungas” with thatched roofs; these dwellings have evolved over the years to take on the harsh climatic conditions of Kutch. Lippan or mud-washing using materials like mixture of clay and camel dung keeps the interiors of the houses cool. Lippan kaam on the outer surface of the homes acts as an insulator by reflecting heat therefore helps keep the interior of the home cool. Inside the home, the inner walls are adorned with decorative mud-mirror work where a single lamp proves enough to light up a considerable part of the home, thanks the light reflected from the glittering mirrorwork. The mirrors used are called “Aabhla” and can be round, diamond or triangular. The mirrors are believed to ward off evil and are therefore found as an integral part of their embroideries and their walls. In about 4-5 days the clay dries off, a layer of white clay, which comes from the marshland sand that is rich in salt content, is painted over the artwork. Though the authenticity of Lippan Kaam lies in a completed piece that is all white or in shades of neutrals; bright colors like red and green are sometimes painted on the dried clay work. Once the walls are completed, they look stunning with mirrors embedded in the mud work, much like the embroideries itself. Some of the motifs are peacock, camel, elephant, water bearer women, women churning buttermilk, temples, mango tree as well as pure geometric patterns.

Mud and mirror work was done directly on the walls of the house by artists who do not use any kind of sketch or markings for reference. The clay used is mud which has been passed through a sieve to obtain fine particles that mix more easily. The camel or donkey dung used acts as a binding agent as it is rich in fibres. Equal proportion of dung and clay are mixed and kneaded to form the dough used for lipan kaam. Some use of husk of Bajri i.e. millet as an alternative to the dung which attracts termites, and the husk does not. Small portions of the dough are taken and shaped into cylinders of varying thickness by rolling between the palms or on the floor. This is then pasted on to the moist surface i.e. the wall or wooden panel on which the decorative artwork is to be done. Each artwork usually starts by using the dough to first create lines that define the boundary of the artwork. The lippan on the walls, partitions, doorways, lintels, niches, and the floors of the bhunga are elaborate bas relief decorations that consist of textures created by the impressions of fingers and palms-and sculpted forms that are inlaid with mirrors.

The Meena tribes of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, India, who claim to be descendants of the fish incarnation of Vishnu, are the first painters of Mandana. Mandana in the local language means ‘to draw’ in the context of Chitra mandana or ‘drawing a picture’. Dating back to the Vedic age, 1500 to 500 BCE these paintings are an intrinsic part of the mud house architecture and painted on walls and floors, both within and surrounding the house, to welcome divinity into the house and keep away from evil forces. In Rajasthan they are painted on walls and the floor but in Madhya Pradesh its restricted to the floor. Mandana paintings can be divided into two types called Vallhari pradhan & Aakruti pradhan. Vallhari Mandanas usually done on walls consists of floral patterns & nature living objects like- birds and animals. Aakriti Mandanas usually done on floors depict geometric forms expressing the five elements of Prakriti (nature) like- triangle (fire), square (earth), circle (water), dot (ether) crescent-curve line (air) and non-living objects. The red clay and the mixture of water and cow dung mark the beginning of the process as it plasters the traditional pattern of the floor. The colors used are red and white, as these abundant in the area. The brush made of twigs, cotton and a small portion of squirrel hair are the paintings tools. Wall paintings by the Meena women are nature paintings without a narrative. There is no ground line so all the motifs float freely. The peacock is their forte and is drawn in several different beautiful ways. There is a specific way to draw and paint the perfect Mandana. First, the exterior walls or floors are plastered with red clay, which is the most crucial element for this type of painting, along with a mixture of cow-dung and water. The motifs, which are almost re-done daily by women from the village, are drawn onto the wall or floor using rudimentary tools such as a brush made of a date twig, a clump of squirrel hair and cotton. Once the motifs are made, they are then filled with color. The color scheme of these paintings is actually very basic i.e., white, and red, and are chosen specifically because they are easily available in the community’s natural surroundings. White paint (Khadiya) is made of chalk while the red paint (Geru) is made of brick. Since concrete houses have been constructed in place of traditional mud houses, this art form is on the verge of extinction as it’s not possible on cement walls. Two villages Tonk and Sawai Madhopur (Rajasthan) are among the few which still daily practice Mandana art.

Nagaland is vibrant with a rich architectural wood craft tradition which has its roots in an animistic past. Traditionally practiced only by male members, the Konyak, Phom and Angami communities are especially noted for their amazing woodcarving skills while the other tribes are distinguished by signature styles with marked differences in the usage and portrayal of designs and symbols. The typical Naga wood carving motifs on the wooden houses are mostly abstractions of animal forms. Human figures or sculpted heads related to fertility or achievements of a warrior in the head-hunting tradition and the Hornbill and the Indian bison or Mithun almost a signature of Naga architecture and can be seen in every village in their magnificence, but degrees of use vary. Other common motifs used are Tigers, Elephants, Snakes, Barbets, Lizards and Monkeys each with their associated symbolism. Often colored in black, terracotta and white pigments derived from natural sources, they proclaimed the status and power of the house owner or the village itself. Characteristics of Naga wood craft is that it’s basically sculpted out of solid trunks or pieces of wood from the Hollock/hollong, Leikai or Teak tree trunks. The Dao or Machete, Hammer and Chisel were the only tools used in woodcarving. These decorative carved elements adorned the village gates, front doors and walls of only tribal chief’s house or of men of social distinction. The men’s dormitories (Morungs) had the most elaborate and impressive of wood carvings and distinct architectural styles and were positioned in special sites in the settlement.

Kerala has the second-largest number of mural sites in the country, after Rajasthan. The Kerala frescos depict deities like Vishnu, Shiva in all their glory along with Hindu mythological tales from the Puranas, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Although it originated in the 9-12th century, the best murals were created between the 14th-16th centuries due to the rise of the “Bhakti Movement” - the patronage of local rulers and landholders, who commissioned these paintings as a way of expressing their devotion. The frescoes of Kerala belong to a class known as ‘Fresco-seco’, characterized by its lime-medium technique where the murals are painted only after the prepared wall is completely dry. These are usually found on the exterior walls of the sanctum sanctorum, the mandapas and the circumambulatory path of temples. The paintings are a highly stylized version of the gods, with wide open eyes, elongated lips and exaggerated eyebrows, like the forms depicted in the classical theatre of Kerala.

The six painting stages of Kerala Murals are :

* Lekhya Karma: On a white background, sketching with a pencil/crayon the contours and curves of the motifs.

* Rekha Karma enhancing the outlines of the sketch.

* Varna Karma breathes life into the painting with colors derived from natural sources – red, yellow, green, black and white. The human figures are colored according to the characters and their virtues. The divine and noble characters are painted in green, those inclined towards power and wealth painted in shades of red to golden yellow. Evil characters in white and demons in black.

* Vartana Karma: Shading process.

* Lekha Karma is adding the black outline to the full painting.

* Dvika Karma is the final finishing touches and details.

Aipan/Aepan floor art, from Kumaon region in Uttarakhand, founded during the reign of the Chand dynasty to celebrate all festivals and rituals ceremonies by decorating the floors and entrances of their homes due to beliefs that these motifs evoke divine power which brings good fortune and wards off evil. The word "Aipan" derivative of a Sanskrit word "Arpan”. The actual meaning of Aipan is "Likhai" that means writing, and it is a pattern that is made with the help of the last three fingers of the right hand. It is passed down from mothers to their daughters and daughter-in-laws and primarily was practiced by Brahmin women. The patterns differ for each ceremony, occasion and according to the deity. The central designs of the Aipan have their own significance and usually comprise of a yantra or a symbol assigned to a particular deity, required to be drawn exactly as it without any changes to its assigned shape and place, while the outer decorative design can be extended or reduced to fit the red background. The dots (Bindu), is an important element without which the Aipan is considered incomplete and inauspicious. Seen above is the “Nav Durga Chauki ”- Durga, the goddess of power and strength, is worshipped for nine days during Dassehra. The central design is drawn at the time of worship is composed of nine Swastikas woven in an intricate pattern called Khoria/Bhadra. The pattern is a square of eighty-one dots which are joined by dashes in a particular order forming nine Swastikas - representing the nine names/forms of goddess Durga and there is a Ashta-dal Kamal (8-petalled lotus) around the Nav Swatika within the larger square and is surrounded decorative borders beyond it.

Aipan art is practiced daily with simple designs and elaborate ritual designs are prepared on ritual and festive occasions which can take months, even when a group of women working on them. The raw material used is simple geru (sienna red clay) for base and rice paste made by soaking any rice for about 16 hours and then grinding it into a fine paste with a medium to runny consistency. The ring finger of the right hand is used to draw the elaborate patterns with help of cotton balls or cloth. The women manipulate their hands with swiftness when the geru base is moist so as to enable smooth painting. The rice paste is easily absorbed by the ground and dries within a short time, leaving a bright white design against the reddish brown background. Generally aipans are drawn with liquid colours but sometimes they are also made with wheat and rice floor and dry-powdered earth colours. Aipans are executed in the courtyard (kholi ke aipan), on the steps leading to the main door of the house (dwar aipan), on the threshold (dehali aipan), in the pooja area, on low wooden stools, on the vedi during sacrificial rituals, on the inner and outer surface of the winnowing scoop, on the outer surface of the pot in which the tulsi plant is sown or on the floor round the mortar (ukhal) which consists of a hollow stone sunk in the courtyard.

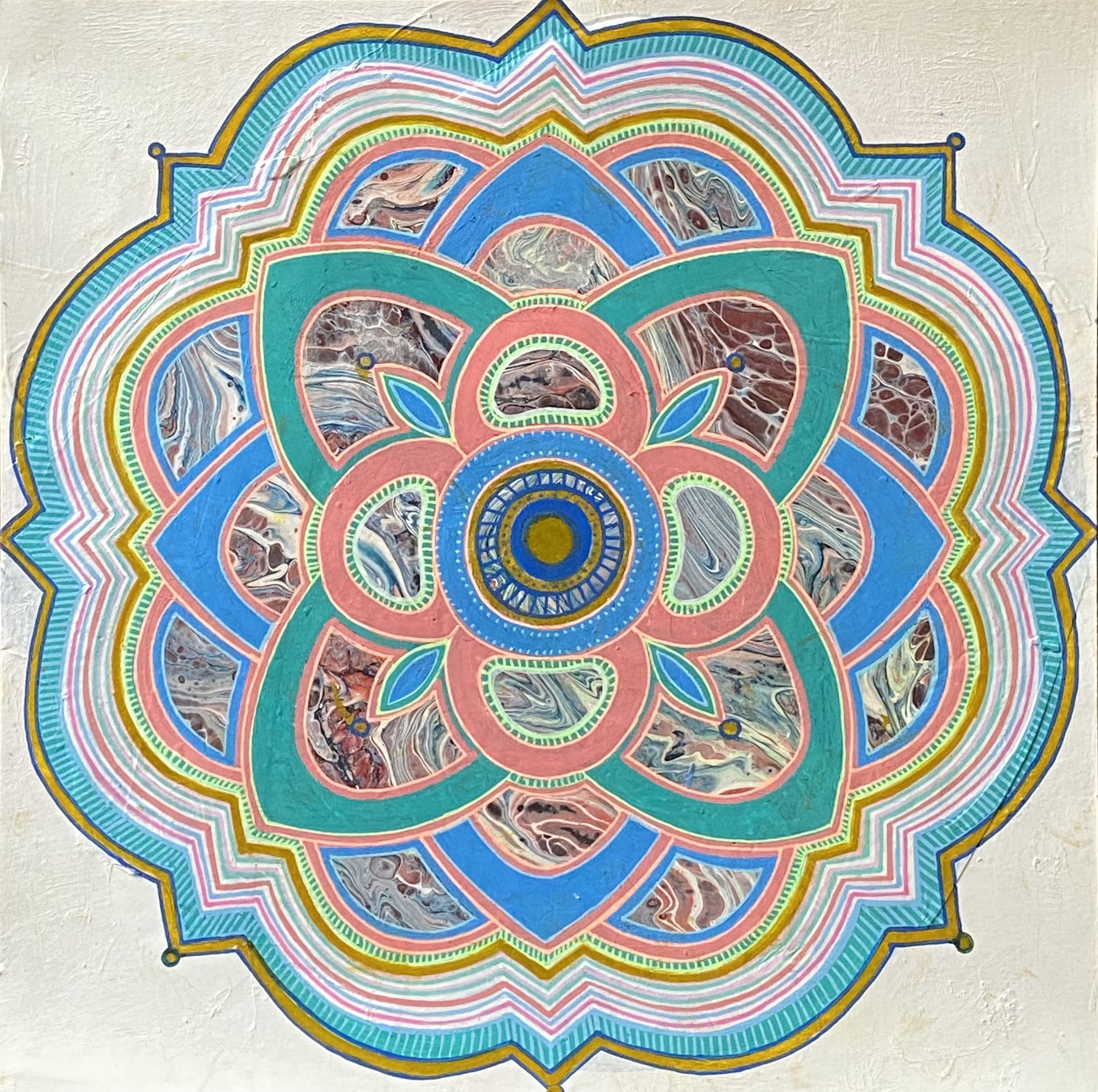

Aripan is floor art of the Mithila region of Bihar. Aripan is derived from the Sanskrit word “Alepan” meaning to smear the ground with cow dung and clay for the purpose of purification of the earth. Initially, these were made as an offering to appease the Gods to make the cultivable land fertile and fruitful but now it has become a part of festivals and each and every life-cycle rituals, including the ceremony of the dead; each have a specific associated Aripan diagram drawn on the courtyard, on the threshold of their houses, and at the entrance gate of their houses.. The Aripan diagrams have a very strong tantric origin. The yantra of the goddess and the red vermillion dots (Rakta-bindu) placed at pre-determined spots in the Aripans, setting them apart from other rangoli art. Rice paste (Pithar), Rice powder mixed with turmeric and sindoor is also used for some Aripans.

Seen here is the Shada-dal and Ashta-dal (six and eight petalled lotus) Aripans, with the Shatkona and Ashtakona yantra respectively is made in the centre of each temple for auspicious occasions to propitiate the mother goddess Bhagavati (Gauri). Mantras, expressing their desires are chanted by the girls while drawing the Aripan. The patterns inscribed in a circular mandala are very cosmic in nature and contains the whole universe including the sun and the moon, the planets and stars, the red dots representing the twelve months, six seasons, the cycle of day and night, the hours, minutes, seconds in a day and also the various symbols and attributes of gods. These aripans are drawn to ensure protection from the malevolent forces of nature and to propitiate the goddess reflecting the prevalence of the Shakti cult.

oth old and young women practice this particular art form and any ceremony or ritual is considered incomplete without this traditional art form adorning the ground.. To create an Aripan, women dip two fingers into the a paste of powdered rice and water, and by graceful and deft movements produce beautiful, geometrical patterns on the mud floor of their homes and courtyards. These patterns also include different design elements integrated into them to thank Goddess Earth. In order to adorn the creations more, the women also smear vermillion (Sindur) red powder/local red clay for red at specific spots of the Aripan; turmeric and flower petals for yellow; leaves for green; soot for black and crushed berries for blue, are used to adorn the Aripans.

The designs or the motifs used in Aripana fall into the following five categories:

- human beings, birds and animals

- flower (lotus), leaves, trees and fruits

- Tantrik symbols, like yantras, bindu (dots), etc

- Gods and Goddesses

- Other objects like lamp, swastika, mountain, rivers, etc.

The sacred art form of Alpana/Alpona, is closely associated with folk rites and rituals and created on the floor before sunset. Alpana originated from a Sanskrit word 'Alimpana', meaning 'to plaster or to coat with' and another version traces its roots to the word 'Alipana', meaning the art of making ails or embankments believed to keep homes and neighborhoods safe. The ritual, usually practiced by women, is also intertwined with an aspect of self-expression. The Alpana patterns remain best documented amongst all the floor arts of India with motifs being ritualistic images from mythology and scriptures and having a purpose to serve. Although, predominantly it is white in color, other hues turmeric paste for yellow and red clay with vermillion paste for crimson can be used. It has an ecological importance too, the rice flour used served as “bhutayajna” an offering to tiny creatures like ants and other insects and rice powder is a cleansing element which is traditionally attributed to preventing chicken pox during the summer and is hence applied on the faces of children in several parts of India as a preventive measure.

There are 4 types of Alpanas:

1. General decoration Alpana consist of abstract decorative motifs which are drawn with no specific intentions and their sole purpose remains to be good luck charms. These are non-ritualistic alpanas drawn every morning or during festival and on auspicious days. The artist may take the liberty of imagination with respect to the motifs drawn in these.

2. Asana Alpanas (Pinrhichitras/Alpanas of seats) - Asana for the deity; Asana for the bridegroom; Asana for the baby

3. Vrata Alpanas : The term vrata means to undergo solemnly certain physical and mental discipline with a view to achieve a desired result or object. These Alpana are highly symbolic and executed in abstraction with the specific intentions for fulfilling the desired objectives. The artist is required to put the ritualistic motifs in their proper shape and place and has no option regarding these factors as the drawn motifs are of great importance in the vrata rite.

4. Alpana of Nagas: The naga cult as prevalent in this region worships an anthropomorphic serpent goddess known as Manasa. Colored powders are used in such drawings and the entire floor of the room appears to be a picture-gallery.

In the Bengali alpanas, generally liquid white pigment made of rice powder is used and made with the help of a small piece of cloth that is soaked in a paste of powdered rice and water but the alpana drawn on the occasion of Maghmandala-vrata dry rice powder with powdered colours are used. The process of drawing designs with coloured rice powder is called gundi chitra.

In Himachal Pradesh, the Pahari women draw many diagrammatic designs called ‘Yantras’ on the thresholds on ceremonial occasions. This form of floor painting is locally known as ‘Hangaiyan’, while the other forms of floor art paintings are Dehar (threshold), Likhnu (writing) and Chauk (ritual places ).

The process involves sweeping the floor and then “Lipna” which is plastering it with cow-dung which, once it begins to dry, is then burnished with a round stone. Sometimes women create foliated borders using finger-tips on the wet coating. The background is painted with brown coloured earth (Loshti). Materials used to paint include rice or wheat flour paste or white earth known as Golu or Makol. Mostly in India, the patterns are normally executed with their fingers by the ladies but the here the patterns can be created using makol involves a different technique. The makol paste is prepared by adding water to the white earthen cakes. It is then filled in an earthen pot with a small hole at its bottom which is then moved by the women so as to create various circular patterns. Sometimes an earthen jar with a spout is used for this purpose. The woman keeps on moving unselfconsciously in a rhythmic formation, spontaneously creating a large bold, fluent and rhythmic pattern. Here, the fingers or hands are insufficient to perform the job, thus the whole body moves blissfully to accomplish the feat. These patterns so formed are necessarily circular with inset lotus symbols.

Shown here is Likhnoo drawn on Aas Navami day

Goddess Navami Parmeshwari (Goddess of hope) is appeased on that day for the well-being of the children in the family. She is believed to possess vindictive dominance over those who defy her rule. According to a tale told on the occasion, once a landlord and his wife who had nine married sons. The landlady deliberately defied the goddess so the goddess became furious and cast a shadow of doom over the whole family. The landlady and her daughters-in-law prayed and on the ninth day of the bright half of the Jyeshtha (called as Aas Navami) the Goddess Navami Parmeshwari’s temper was calmed down so then from that day onward all married women worship her. The characters of the tale find a symbolic representation in the drawing made on the floor on this day. Eleven figures representing nine sons, the landlord and his wife are drawn in a quadrangular frame, symbolizing the earth. A figure of an attendant is also drawn in the notch left out at the bottom of the frame. The sun and the moon also find a place in the frame of the earth, symbolizing cosmic unity. In two small pockets drawn within the frame, eighteen spots are marked as offerings to the goddess.

A tradition passed from mother to daughter in Uttar Pradesh, chowk means "auspicious area of home” whereas purana means "drawing on floor/wall." Designs in square forms are generally known as Chowk. The process of making chowk is referred to as Chowkpurana. The square chowkis are made for glorifying deities like Lakshmi, Durga and Saraswati. These designs have symbolic motifs like the dot signifying the absolute, with a number of concentric circles depicting growth and expansion. These are nearly always associated with a ritual. Besides the chowks, general floor patterns drawn on various occasions are also referred to as Sona Rakhna. Some of the festivals when chowk art is drawn include Raksha Bandhan, Devthan Puja and Holi.

The night before painting the mud walls, geru is mixed with water to be spread over walls and the floor. Rice is soaked in water on the day of the painting, then finely ground and mixed with water. Geru is "spread in a square or rectangular shape depending on the occasion and after that the design was drawn." Women draw sketches using dots to draw the outline which would then be connected with lines using chalk powder on wet ground, or rice paste on dry surface. The art is drawn on religious and social occasions. The art of Chowk Purana in Uttar Pradesh is practiced by women on festivals and happy occasions. a specific type of Chowk art - When art is drawn at the threshold of a house on a wedding, the art is called Chetrau or Chiteri which incorporates an image of Ganesh. The colours used to draw a Chiteri included yellow, blue and green.

In Punjab, chowk-poorana refers to preparing the square on the floor with flour and turmeric on weddings and other religious ceremonies, symbols like planets, floral, geometrical designs and Om are drawn for worshipping are drawn on mud walls and in courtyards using powdered colours or earth colours such as White, Ultramarine Neel and Indian Red Gerua. The patterns are created using a piece of rag. These patterns tend to be very simple in comparison to the intricate designs of mandana paintings in Rajasthan and Gujarat. There are different types of chowk but they all start as a square made with flour and then design can be made within the square such as circles or triangular shapes. Dots are drawn using red sindoor (Vermillion). A Phulkari chowk is when designs drawn are the motifs used on Phulkari embroidery. Green is used for the branches and leaves, and white, red and yellow is used for the flowers. Modern squares are more colorful and use rice as well.

“Rut Raade” is a Dogra folk festival of Duggar is celebrated for centuries throughout the Jammu region. The reasons behind the celebration is that the farmers sow the seeds of various crops before the onset of monsoon to find out the quality and viability of the seeds and to see which plant will grow better in the given climatic/weather conditions and then they would sow the seeds of that crop to reap a rich harvest. Another belief is that these seeds are sown by the unmarried girls who are treated as the symbols of Goddess Laxmi so that the family be bestowed with the blessings of the Goddess for a good harvest.

The term Raade refers to the rims of broken earthen pots which, on this day, are arranged in a circle representing the number of males in the house. Unmarried girls draw colourful floral and geometric designs around these raades every Sunday evening for a month with the natural colours obtained by crushing bricks, charcoal, turmeric, flour and ground rice and dried leaves of plants. As the seeds sprout into saplings these raades are protected and watered everyday. The girls eat their food collectively placing their thali over the rade and sing folk songs related to the ceremony. After the month long festival is over the raade is taken out and the grain saplings are sown in the fields by the brothers.

Mandana is a ritual art bearing some characteristic differences of the region from where it has originated. There are seven main festivals on which elaborate floor patterns are made - Deepawali, Makar Sankranti, Holi, Gangaur, Bar Pujani Amavasya, Teej and Rakshabandhan. The courtyards, floors of the verandah, rooms, steps, parapets, water- stands and stoves are replastered and decorated with Mandanas. The wall decorations on the mud walls of their houses are called Thapa. Though the technique of Thapas is similar to Mandana -the major difference lies in the motifs used. The Thapa motifs consist mainly of the animals, birds, flora and fauna of the region whereas the motifs of the floor mandanas are highly symbolic with definite meaning and purpose. These are mainly geometric patterns drawn without any tools or grids and comprise of three main parts:

* A main central motif with a specific name, is enclosed within a circle or a series of lines (Dora) drawn, parallel to the lines and angles of the original motif.

* The “Laddus” surrounding the central motif and empty spaces are filled with “bharat/bharana” oblique parallel lines, dots, small alternate squares making a chess-board design depending on the region and artist. (Not shown here)

* To fill up the residual space around as well as to enhance the beauty of the central motif design smaller independent forms of motifs called the “Chhota-mota mandana” are made. These are objects scribed as per the occasion signifying the associated customs and rituals.

One of the myths associated with the origin of Mandana floor painting popular in these regions, links it with Shiva’s consort Parvati – Once Shiva and Parvati had an argument when Shiva challenged her to make the courtyard of their house glitter and dazzle with splendor or else he would retreat to the Himalayas for four months. If she succeeded, her art would spread in the world and be known by her name”. Parvati had an idea to mix together cow dung and clay and smooth it over the courtyard to fill up the cracked and flacking surface. When Shiva returned he found the house sparkling clean but it still did not dazzle with splendor. He called out to Parvati and said: “You could not keep the promise. I am leaving for the Himalayas”. Parvati, who was inside the house, ran after him to stop him and as she did that, she left numerous foot-prints on the still wet ground and the courtyard began to dazzle as if filled with beautiful flowers. Shiva was astonished and he said: “From now onwards these mandanas would enhance the beauty of the houses and in whichever house they would be map, I would come to reside there and the household would prosper forever”. Since then, after the house has been given new coat of mud and dung, mandana designs are drawn on it. One may step on to this freshly plastered ground only after the mandanas have been drawn.

Floor art in Orissa is known by various names like Jhoti, Chita, Osa and Muruja.

Jhoti/Chita is a traditional Odia white art used to decorate the house walls and floors and maintain the religious and ritual heritage associated with it by specific patterns. The Jhoti or Chita is believed to establish a relationship between the mystical and the material, thus being highly symbolic and meaningful. For each occasion a specific motif is drawn on the floor or on the wall using is a semi-liquid paste of rice, the fingers become the brush to make it or one can draw with a piece of cloth surrounded with a stick to create beautiful Jhotis. Most of the patterns have a motif of two feet seen in the center implying the pious entry of goddess Lakshmi into the home. Lotus is an important symbol associated with the goddess along with the conch shell is used in all pujas.

The term “Osa” in Oriya means vrata (pious observance) and hence the floor designs related to vrata rituals are referred to as Osa. These are made out of rice paste and may be round or square mandalas depicting assemblages of objects.

Muruja is white powder or fine sand with colour added to it . Muruja is generally used in November during rituals in the forms of mandalas, a sacred geometric figure representing the universe on the pedestal of Tulasi (Holy Basil plant ) with coloured powder.

The tradition of making Gahuli (Rice Swastika) by followers at Jain temples in front of Jain deities or on religious events as a sign of good omen or auspiciousness. Swastika is an important symbol in Jainism, Hinduism and Buddhism. In Jainism, the four arms of the Swastika symbolize the four states of existence, namely, heavenly beings, human beings, hellish beings, subhuman like flora or fauna as destined to one of these states based on their karma. It symbolizes that one has to rise above the running cross of Swastika, meaning that one has to transcend imperfect world to a permanent state of enlightenment and acquire the four characteristics of the soul: infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite happiness and infinite energy.

In Sanskrit, the word Swasti is composed of 'su' - meaning "good, well" and 'asti' meaning "it is", which thus stands for the "thing that is auspicious”.

According to the scriptures every Jain has to draw them with pure un-broken rice grains before the icon of the Tirthankara. To make rice gahuli, first of all the rice is spread on the floor in square, circular of hexagonal shape. Then successively the first finger is run in the rice in cyclic order to get the Swastika design in simple or complex designs. It is widely known as an important symbol used in Indian religions, denoting "auspiciousness."

Poovidal or Pookalam ritual of creating flower mats on the floor in front of the house continues for all ten days of the Onam festival in Kerala. “Poov” means flower and “Idal” means arrangement, and Kalam means drawing. A basic design begins on the first day and increases each day making a huge Poovidal for the main day of festival. A traditional Pookalam consists of the “Dashapushpam”meaning ten flowers each making one ring to honour Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati, their sons Ganesha and Kartikeya, Lord Brahma, and last but not the least, the Vamana Avatar of Lord Vishnu and King Mahabali. Therefore, the symbolic meaning of the pookolam is that it is not just a decorative pattern but a symbol of divinity and these flowers are believed to have medicinal qualities. The flowers used are specifically associated to the deities are

* Thumba Or Ceylon Slitwort: the small white flowers

* Tulasi or Holi Basil: Lavender flowers

* Chethi Or Flame Of The Woods: Red flowers

* Chemparathy or Hibiscus or Shoe flower: Dark red colour

* Shankupushpam Or Butterfly Pea: Deep blue colour with yellow

* Jamanthi Or Marigold: Yellow flower

* Mandaram: White and yellow

* Kongini Flower Or Lantana: Multicolored

* Hanuman Kereedam Or Red Pagoda Flower: White and red

* Mukkuthi: Dark yellow colour

In Maharashtra, it was and still is a custom to draw a symbolic white rangoli in front of the house in the mornings. The floor Art “Rangoli” is drawn on the threshold (umbartha), in front of the Tulsi plant, in front of the Gods and the one drawn at the entrance. The traditional Maharashtrian rangoli is geometrical in style where designs are drawn by first making the dots and then joining them to make figures and finally filled in uniformly with powdered colours. Sometimes turmeric and kumkum (Vermillion) dots are marked in the white rangoli to make it attractive and auspicious.

Seen above is a Rangoli drawn only by the Chitpavans or Koknastha Brahmans in Maharashtra during the religious ritual of of “Bodan”. This symbol is also found on the Ganesh-patti on top of the entrance doors of some houses in Konkan. This is made in the center on which the paat (low stool) is placed then the puja of the goddess is performed on this past by the ladies on various occasions like birth, Upananayana, marriage, new house and even after fulfillment of certain wishes (navas). In some families it is an annual ritual to be performed to please the family Goddess and seek her blessings.

In the Konkan region of Maharashtra, where rice grows in plenty, rangoli is made out of rice husk. Rice husk when burnt slowly, converts into a fine crystalline white material which is used as rangoli. This powder is very popular as it is made out of waste material- rice husk and therefore easily available and cheap. It is also used for brushing teeth and cleaning utensils. The powder obtained from stones (shirgole or gote) found near the river is also used for rangoli.

In the Ghats and Desh region quartz (kachmani) or silica sand and lime-stone powder (chunkhadi) is used for rangoli. Mixture of fine and coarse silica sand was used earlier but in recent years the white silica sand is filtered through sieves and cloth to obtain a fine mesh of spreadable sand.

Serpent God is a symbol of fertility and life and serpent worship is common among the Hindus all over India. Coastal Karnataka has an all night ritual performed during December to April. Snakes are considered auspicious and one can find these nagamandalas drawn on the floor or carved on the wall/pillars of temples in many parts of India. Nagamandala is Naga which means serpent and mandala implies decorative pictorial drawings on the floor. Nagamandala depicts the divine union of male and female snakes where a pattern is formed of a "snake which weaves itself " into a number of knots called "nagabandha" (snake knots ). It is a highly intricate and complex motif created out of knots (pavitra), depicted by the entwining snake. A full mandala is made up of sixteen knots. Twelve knots make three-quarters of a mandala, eight knots comprise a mandala and four knots form the quarter mandala.

The dance ‘naaga’ takes place around this ‘mandala’ drawings. The all night dance and song propitiation creates an awe inspiring experience. Brahmins utter the mantras in sanskrit and the other proceedings take place in Kannada.

The drawings in five different colors on the sacred ground are drawn by only the Vaidya community group. The five colors are white (white mud), red (mix of lime powder and turmeric powder), green (‘jangama soppu’ green leaves powder), yellow (turmeric powder) and black (roasted and powdered paddy husk) used in the Nagamandala drawings. The combination of these five colors is called as ‘panchavarnahudi’ in the local dialect.

The snake coiled in the panchavarna rangoli, daylong homas and night long dance of the nagapatri and nagakanika, whose dance movement depict courtship are symbols of fertility and prosperity. The leg movements of the dancers are imitative of the excited snake. The rangoli is obliterated by the dancers in the act of dancing. After the ritual the rangoli powder and the betelnut flowers become the prasadam for the gathering witnessing the ritual.

Rangoli in Andhra Pradesh is called as Muggu (the plural is Muggulu).

The muggu consists of geometrical patterns or dots, which are joined by lines or curves that have a mathematical calculation. So it can be inferred that ancient Indian women had artistic traits combined with a sense of arithmetic, which they represented in the drawing patterns of the muggu. The patterns of muggu are very complicated and huge during festival months. The temples usually have complex patterns that cover thousands of square feet and created by several women working together thus bringing in the spirit of team work and speed and these are considered as “painted prayers”.

There are different types of Muggu:

* Chukkala Muggulu (Dot Designs): Dots are arranged in a specific sequence, in a matrix form equidistant from each other and these dots are joined either by lines or curves to create different muggu designs. A chukkala muggu in plain white muggu pindi (white rangoli powder) created in the courtyard of a home. Sometimes after the creation of the basic muggu in white muggu pindi (white rangoli powder), various coloured rangoli powders are used to fill in the pattern to create a decorative look for special occasions.

* Chukkalu leni Muggulu (Designs without dots): These designs are made without dots. They are similar to free hand drawings of lines and curves, but use occasion specific elements to make different muggu patterns.

* Tippudu Muggulu (Curved Designs): A basic matrix of dots, equidistant from each other is created first. Then twisted chains are created around the dots in an expert fashion to create exquisite, symmetrical muggu patterns.

Muggulu are believed to bring prosperity to homes and on festive occasions it is drawn in every home. Every morning before sunrise, the women folk clean the entrance to a home and/or the courtyard with water, considered the universal purifier, and the muddy floor is swept well to prepare an even surface. Cow dung is mixed with water and this slurry is expertly sprayed on the requisite area and spread evenly with a broom. This is done on a regular basis in rural areas, and on festive occasions in certain urban areas, where there is availability of sufficient cow dung, and space to draw the muggu. This procedure is performed as it is believed that cow dung has antiseptic properties and hence provides a literal threshold of protection for a home. The muggu is then drawn on this prepared surface. The dark colour of the cow dung slurry also provides a good contrast for the white powder of the muggu.

Muggupindi is a mixture of calcium and /or chalk powder which is used for creating these exquisite and unique muggu patterns. It’s a slightly heavy powder that falls thickly across the wet earth and stays in form while being used. As the index finger and thumb clasp a tiny bit of it and start dropping it from half an inch above the wet floor, the white powder falls gently leaving a white trail behind. There is a knack of letting this powder flow smooth and even, as one draws lines and curves of the muggu designs. During festivals rice flour is used to create the muggu, instead of the muggupindi as it is considered as an offering to the ants, insects and sparrows that tend to feed on them.

In Tamil Nadu, the drawing of a kolam forms an essential part of the daily work routine of women. Normally, kolam is drawn twice, once at sunrise and again before sunset. The kolams of each occasion vary from each other and are drawn with a specific purpose. Wet paste of rice flour is used to trace the design on the floor is called Makolam which are sometimes outlined in red with kavi, a red brick paste, to make it look grander and more beautiful. The auspicious combination of white and red ensures fertility and warding off of evil. Sometimes, powdered quartz or slaked lime is also used. In Chettinad, all kolams are bordered by double rows of dots. The dots are considered as couples and hence are representative of the dual aspect of a whole. Only on inauspicious occasions a single row of dots adorns the kolam.

Shown here is a variation of the “Nalvaravu” (Welcoming Kolam) which is drawn on the threshold of the house welcoming people at the meeting point of the external and the inner space of the house. Sacred symbols are drawn such as the Lotus for prosperity, Conch shell which has its genesis in water and water is taken as a life force which is needed for sustenance in any household and the lamp signifies light therefore the removal of darkness (symbolic for ignorance). There is a center grid around which depending on the requirement, imagination, space availability the design is drawn. By creating the Kolam a sacred space has been defined and that space is further bound for auspiciousness by the color red as well as to heighten the contrast.

Every Kolam has its own place and its own meaning and significance. Nalvaravu, (or welcoming kolams), indicates that a home is open to visitors and friends. They are especially used to welcome guests to a home or venues where celebrations are being held. This kolam uses the element lotus on the fringe ends of the kolam, which is a symbol of the sacred. Elements like the conch which has its genesis in water are also used. The lamp is dispeller of the darkness. After the kolam is drawn it is bound by the red coloured kaavi. This defines the sacred place that has been prepared with all pure intention. The colour red of the kaavi is the colour of prosperity and aesthetically speaking it heightens the contrast of the kolam.

1. A basic grid is drawn at the venue before the kolam is created.

2. After the central square the side squares are decorated.

3. The squares in the grid are filled with horizontal and vertical lines.

4. The squares are connected with curved lines.

5. The central square also gets connected to the side squares with a short set of lines

6. More curved lines are built around the central pattern to develop the kolam.

7. More elements are added beyond the curved lines and to the periphery of the kolam.

8. The red kaavi is used to create a bold outline along the kolam exterior.

9. The red kaavi instantly heightens the look of the white kolam.

10. The completed kolam that waits to greet the guests at the venue.